Apr

15

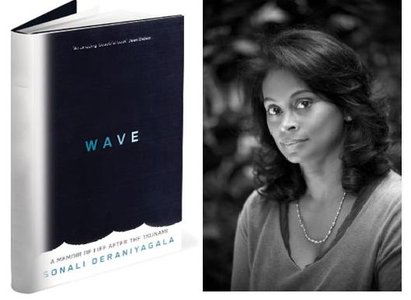

In Wave, Sonali Deraniyagala chronicles the events and aftermath of the Sri Lankan tsunami that killed her parents, her husband, and her two young sons. They had all been staying at a beach hotel together on December 26, 2004, when they were swept up in the water. Only Deraniyagal survived.

It sounds horrifically sad, doesn’t it? It is, of course, but maybe not quite in the way you’d expect. Deraniyagala describes her early months of grief and confusion with such unflinching, precise style it takes you somewhere deep inside her experience. You’re not standing on the outskirts wringing your hands at the unspeakable tragedy that’s occurred, you’re immersed in it, somewhere beyond the tears.

Cheryl Strayed has a great review of Wave in which she writes, I didn’t feel as if I was going to cry while reading “Wave.” I felt as if my heart might stop. Yes.

It seems like the first chapter, focused on the actual events of the tsunami and her surreal rescue, would be the hardest to read, but it’s about halfway through, when Deraniyagala emerges somewhat from the muffling shock and suicidal despair and begins to process her losses, when her writing became so powerful — her guilt, her helpless rage, her raw pain — I had to keep putting the book down. Read a page, put it down. Breathe. Repeat.

I don’t have the ability, really, to tell you about the beauty of how Deraniyagala slowly allows herself to stop repressing the memories of her family and, bit by bit, breathes vivid new life into what was. She does it so exquisitely each page fairly resonates with the galloping footsteps of her children. The sizzle and pop of her husband cooking mustard seeds for dhal. Her old life rendered in fullness, while never stepping back from that yawning abyss of its absence.

Towards the end, she writes,

Seven years on, and their absence has expanded. Just as our life would have in this time, it has swelled. So this is a new sadness, I think. For I want them as they would be now. I want to be in our life. Seven years on, it is distilled, my loss. For I am not whirling any more. I am no longer cradled by shock. And I fear. Is this truth now too potent for me to hold? If I keep it close, will I tumble? At times I don’t know. But I have learned that I can only recover myself when I keep them near.

There is no mawkish sentimentality in Wave, no reminders to hug your children, savor every moment, or embrace the comforting notion of a divine plan. It’s honest and vivid and intimate, a great suffering and a slow healing, somehow a nightmare and a gorgeous dream all at once.

It’s unforgettable. If you get a chance, read it.

Apr

9

Dylan was screaming in pain, the sort of fear-driven sobbing that’s hard-wired right into your nervous system, zero to panic in nothing seconds flat, and I was trying to calm Dylan and assess the damage while also turning my head to vent my frustration in Riley’s direction. Technically an accident but also pure carelessness on Riley’s part and goddammit I’d just said — Just said! Just! Said! — not to slam the door while they were playing and he’d done it anyway, right on his brother’s fingers. I wasn’t sure if bones were broken and a deep sliced-open pinch of flesh on Dylan’s knuckle was dripping blood and it was just one of those moments, everyone yelling and crying, total shitshow.

Later I scolded Riley for not listening, not being more careful, not even sticking around to make sure Dylan was okay but bolting out of sheer self-preservation. He was nodding and round-eyed but also maybe getting a little lippy about being on the receiving end of a lecture: “Okay. Okay.” You know that bullshit? Okay my ass. You don’t get to be TIRED of being in trouble. You put something in audible italics and I’m going to be in your face for like ten more hours, just repeating my various points over and over while you agree with FULL SOLEMN ENTHUSIASM EACH TIME.

Anyway. I went to bed that night filled with all sorts of murky worries about empathy and selfishness and taking consequences seriously. I was thinking, I need to know this *means* something to you. It hadn’t seemed to, is the thing. It was like he was upset about us being upset with him, not upset that he’d hurt his brother.

But the next night when I was tucking him in his eyes suddenly pooled and tears ran down his cheeks and he cried out, “I just feel so bad about Dylan.” And he wept that he was sorry and I held him and said that I understood and I told him that we all make mistakes that we feel bad about later and sometimes that’s just how we learn to make better choices. “Even you?” he said in a watery little voice and I kissed him a million times. A billion. Oh, buddy. Yes.