Nov

4

A while ago I read an article about a group of parents who were all pissed off because their kids were being exposed to the Pledge of Allegiance. At first I thought this had to be about the “under God” part, but it turns out the issue is with the notion of pledging your allegiance to one particular country.

The fuss is happening at the John Stanford International School, which is a public elementary school that offers a dual-language immersion programs in Spanish and Japanese, and sports “interior design elements reflecting a world culture.” Sounds like an interesting, progressive environment—and apparently until recently they’ve been been the one special snowflake school that doesn’t observe the Pledge. Even though it’s been mandated by district policy and state law for years.

A new principal decided that John Stanford needed to start following the rules, so an announcement went out to parents that the students would start reciting the pledge every morning. You know, just like every other kid in every other Washington school.

Naturally, because this is Seattle, some parents freaked the fuck out. A mother of a six-year-old said, “It pains me to think that at a school that emphasizes thinking globally we would institute something that makes our children think that this country alone is where their allegiance lies.”

Another parent apparently opposes the flag itself: “But it’s ‘I pledge allegiance to the flag,’ not even the country. I don’t think we should be making kids stand up and pledge to any one thing. It just totally goes against what this community is about.”

Yet another parent wrote in to say, “The pledge of allegiance is forced patriotism. It is indoctrination. The principal’s decision doesn’t take into consideration the diversity of cultures, values, nationalities of JSIS families and staff. And then there’s the ‘under God’ part…”

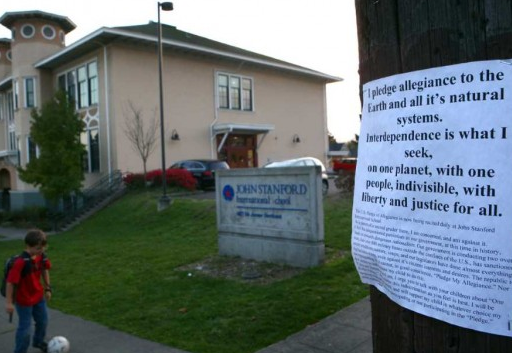

The policy went into effect in October, at which point flyers started showing up on posts near the school:

Photo credit Joshua Trujillo/seattlepi.com

I cannot even make this up: the flyers read, I pledge allegiance to the Earth and all it’s (ARGH POSSESSIVE APOSTROPHE FAIL) natural systems. Interdependence is what I seek, on one planet, with one people, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

So, okay. I can understand feeling uncomfortable about the “under God” section, which was just added in 1954. I can understand if you don’t want your child to have to say something he or she doesn’t believe in. I can understand advocating that the laws be changed about the pledge, if that’s what you’d like to see happen. But I cannot begin to understand how anyone thinks their school is so unique it shouldn’t be subject to the same laws as the rest of the state. Nor can I figure how these words are offensive to the various cultures in our country.

I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America, and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty, and justice for all.

I mean, are we not united, regardless of race, creed, religion, etc? Is it really so bad to remind ourselves that we’re in this mess together? Hell, I’m no traditionalist, but I like the idea of Riley’s super-diverse (like, way more diverse than this John Stanford International School, according to student demographics) school saying the pledge—to me it’s less RAH RAH GO TEAM AMERICA ALL OTHER COUNTRIES CAN SUCK IT, and more of a statement that we remain undivided, even when everything seems to be falling to shit around us.

Here’s the part that really makes me crazy about this whole thing: if students who don’t want to participate in the pledge THEY DON’T EVEN FUCKING HAVE TO. They’re allowed to quietly sit or stand, whatever they choose. No one’s forcing them to say it, no one’s forcing them to believe it. So what the hell?

What do you think about all this? Are you for/against the pledge in your kid’s school?

Nov

4

Fiction Friday: FENCES

Filed Under Uncategorized | 95 Comments

This one’s been posted before, but I’m trying to get back in the habit. Maybe next week I’ll post a follow-up to this.

FENCES

The fly gets my attention soon after takeoff. It seems odd, a fly in an airplane. It makes me think of creaking openings in the body of the 747, entrances and exits that no one knows about. It’s stuck down between the rubbery seal of the window and the metal rim, its wings a tiny anxious blur.

I try to flip it out with the pen I’m using for the crossword puzzle but it’s hard to reach across the empty window seat; the fly gets wedged in there tighter. Or maybe I killed it somehow, because now the fly just lays there, silent and still.

Well.

“Do you want anything to drink?” A smiling face appears above me, her teeth practically glowing in the dimmed cabin. She’s offering me a foil packet, some kind of snack. Probably not peanuts, I figure: peanut dust. Anaphylactic reactions, people clawing at their throats.

“Water, please,” I say. I put the packet – I was right, it’s some kind of pretzel mix – in the seat pocket in front of me, and turn back to the crossword, pretending to be engrossed. (I don’t want eye contact: her smile is about to turn pitying, her eyebrows about to crumple in sympathy.)

Two hours until I arrive in San Francisco; it already feels like Denver is a million miles behind me. My house, my job, even my goddamned dog.

The in-flight movie seems garish without the headphones, without the sound to tell me what’s going on. People gesture at each other wildly, their faces contort into cartoonish expressions. A girl stares longingly at a boy; the camera inexplicably pulls back in a long dizzying swoop to show a lush green landscape.

I can’t keep watching, it makes me feel like I’ve been dropped into a dream where everything is just this side of normal and nothing makes any sense.

A man a few rows ahead breaks into a harsh series of barks, it takes me a moment to realize it’s laughter. I noticed the guy earlier: florid, his chest a husky barrel turning to fat. The ghosts of a thousand dead cigarettes coating his voice. His wife wheezing behind him like a Pekinese. Heart attacks waiting to happen.

I think of all the cigarettes I never smoked, all the drinks I’ve waved off. Got an early run planned before work, I’d say. The fucking picture of health. The guy you rolled your eyes at while you finished off a pint. Whatever, man.

The smiling face is back. She hands me a cup of water, asks, “Can I get you anything else?” while bending over slightly, her perfume surrounding me like a friendly little pink cloud. She’s pretty, in a bland California kind of way. Blonde, the right curves, all that.

Yeah, I think.

Get me a bottle of Jim Beam, because tomorrow is going to be just like today. No early morning milk runs, no sunset Copper Mountain runs, no runs. No goddamn runs.

Get me off this plane, drop me at thirty thousand feet so I don’t have to go to Glen Park, so I don’t have to come home to my parents like this, broken and useless.

Get me a do-over. That’s all I want, really. Just one. Lousy. Do-over.

“No,” I say. “Thanks.”

She cocks her head, beams at me and nods. And I see exactly what I didn’t want to see: an expression that clearly reads, that poor son of a bitch.

She moves down the aisle and I watch her. My face feels hot, my teeth are clenched. I allow myself to imagine jumping up, pushing her into the lavatory, one hand on her hip, one in her hair, walking her backwards into the wall, hard. Don’t look at me like that, I’d say. Don’t. Her face all O’s of surprise and shock.

Right.

When the doctor at Centura first talked to me, used the words catastrophic damage, I didn’t even think about walking. I asked about skiing, not walking. I remember his set mouth, the slight shake of his head. Later, at the Craig, there were a hundred other sorry sacks of shit just like me, everyone with their own catastrophic damage. Everyone wondering just how long the list was, exactly, of things they would never do again.

Mine includes skiing, walking, riding a unicycle, and chasing down stewardesses into airline lavatories.

I close my eyes and do the trick I learned in physical therapy: I picture a wall of black, which I turn blue, then red, then purple, until I stop thinking. When I open my eyes again my ears feel full, the plane is descending. Soon we’ll be landing, and I’ll wait until everyone else disembarks. Then another smiling face will push a narrow-backed aisle chair towards me, the one that’s got DEN stenciled across the front and collapses like a broken umbrella to fit perfectly, cruelly, into the overhead compartment.

My parents will be waiting. They’ll look nervous, they’ll look old and tired and scared. My fault, my fault. I know how I’ll look to them: skinny, years of ski bum coloring bleached pale from fluorescent lighting, shadow-crescents beneath my eyes. They’ll take me home to their house in the southern edge of the city’s hills. Until you’re better, my mother said, back at Craig. I had laughed: better?

I pull my seat upright and fold up the Post – the crossword grid almost entirely empty – and my pen falls to the floor, rolling into the aisle. I reach for it but I can’t quite get there, I need to rise up on my legs a little and of course I can’t. I feel like a dog who’s abruptly reached the end of his chain, surprised anew at my boundaries.

I wonder when these tiny frustrations will finally become familiar to me.

“Here you go, buddy,” says a gravelly voice over my left ear. I look up and it’s the heart attack guy, returning back to his seat. He stoops with a grunt, then straightens up and holds out my pen. For a minute I can only look back at him, how he’s just standing there like it’s no big deal.

Everything is just this side of normal. Nothing makes sense. I am going to have to learn everything all over again.

“Here you go,” he says again, impatient. I reach out my hand and take the pen. I tell him thank you. There is the tiniest of movements to my right that catches my gaze: it’s the fly, no longer trapped, no longer dead. I watch it walk along the edge of the window, and then it takes off. Inside the confining metal tube that makes up its world, it soars away, out of view.